For the descendants of the survivors of the transatlantic slave trade, our family histories are cruelly locked in a vault of time by no fault of our own. Just five generations ago, African families were torn apart in the name of hate and greed. Their seeds were scattered across the globe indiscriminately, leaving souls homeless and hungry for roots they were forced to leave behind. As a Black American, I carry the weight of cultural genocide in my bones everyday, wondering what life would be like if my stolen history, traditions, and rituals were known to me from birth. Holidays like Juneteenth, which commemorates the day Black folks in Texas were notified of their freedom two years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, are designed to do just that: give everyone an opportunity to show reverence towards one of the cruelest portions of American history. But instead, it appears everyone just enjoys the day off.

If it were up to me, Juneteenth would be a day of nationwide grieving mixed with philanthropic work aimed towards the betterment of Black Americans. But I digress. I personally use the day to commemorate the untold stories of our ancestors, a passion I share with one of my best friends, fellow journalist Amber Smith. Amber and I met in our dorm rooms as artsy, bright-eyed, teen coeds at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles about 16 years ago. I was immediately at home in her warm aura and angelic demeanor. Our shared passion for the arts, comedy, and healing gave our friendship its foundation, but obviously, our mutual Blackness was a strong anchor of sisterhood in a sea of whiteness at our college.

As we’ve evolved from our teens into our mid-thirties and gotten to know each other more deeply, I started to track all of the unique synchronicities we share. For example, Amber’s closest first cousin has the same name as me and spells it basically the same way (with an extra R). We both have deep roots in the South, her family hailing from Louisiana and mine from Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina. And even astrologically we are a match made in heaven. I’m a Leo with a Scorpio rising and she’s a Scorpio with a Leo rising. We share a Scorpio moon (intense feelers). We also both share a deep, insatiable longing to know more about our roots. After all, how can you really say you know a friend if you don’t know their origin story?

If it were up to me, Juneteenth would be a day of nationwide grieving mixed with philanthropic work aimed towards the betterment of Black Americans… I use the day to commemorate the untold stories of our ancestors.

A few months back, I got lost in a rabbit hole on friendship and natural selection. A 2014 paper, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that people tend to pick friends who resemble them genetically, as if they were a third or fourth cousin. Lead co-authors of the study, Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler, describe friends in the paper as a type of “functional kin.” Christakis, author of ‘Blueprint: The Evolutionary Origins Of A Good Society’ said in an interview with Unbothered that friendship is “a long-term, non-sexual relationship with a fellow member of our species that is not our kin,” which is an exceedingly rare behavior when we look at the animal kingdom as a whole.

Christakis said that while most of us are aware of the rare phenomenon of “love-at-first-sight,” “like-at-first-sight” is way more common, and something we can experience with our friends. “That feeling of like-at-first-sight is also probably shaped by natural selection,” Christakis said.

“When we call our friend, brother or sister, it’s a kind of an ancient tendency,” according to Christakis. “You’re picking as your friend someone who could be your sister, could be your third cousin, your female cousin,” even if they are not. After nerding through the data, I started to get curious about my friendship with Amber, wondering if our “functional kinship” extended into real kinship, given our shared histories.

So I solicited the help of Ancestry.com genealogist Nicka Sewell-Smith to find out. I had submitted a DNA test to the site a few years prior, so we had a kit sent to Amber’s house for her to do a swab, too. After weeks of anxiously awaiting the results, they came back, and Amber and I held hands tightly in anticipation, glued together on the couch as Sewell-Smith shared with us the secret history of our friendship over Zoom.

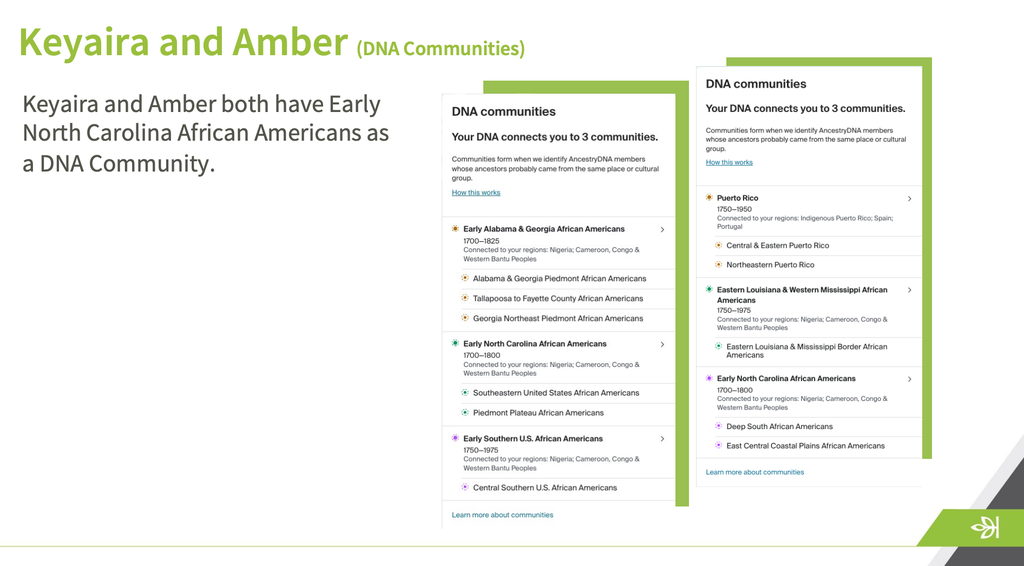

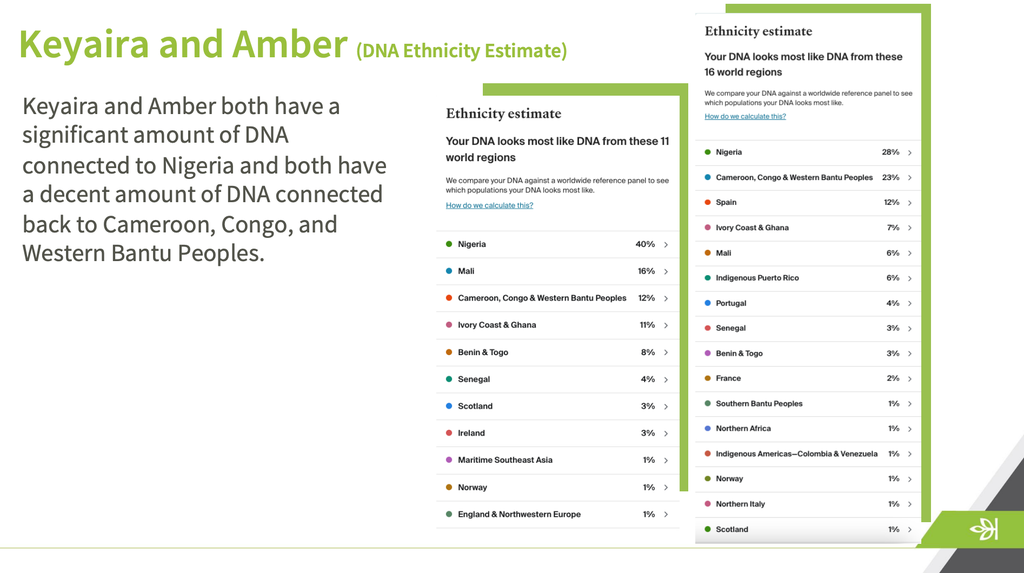

What we discovered is that while Amber and I aren’t genetically related (Amber was actually related to Sewell-Smith, ironically), we do descend from similar African countries like Nigeria, Cameroon, and Mali. Now, that’s not super-suprising given that the majority of slaves in the U.S. were captured from West African countries. However, I do think the fact that we are both journalists is a sacred nod to our West African griot heritage, which is built on a tradition of oral storytelling that keeps African legacies alive.

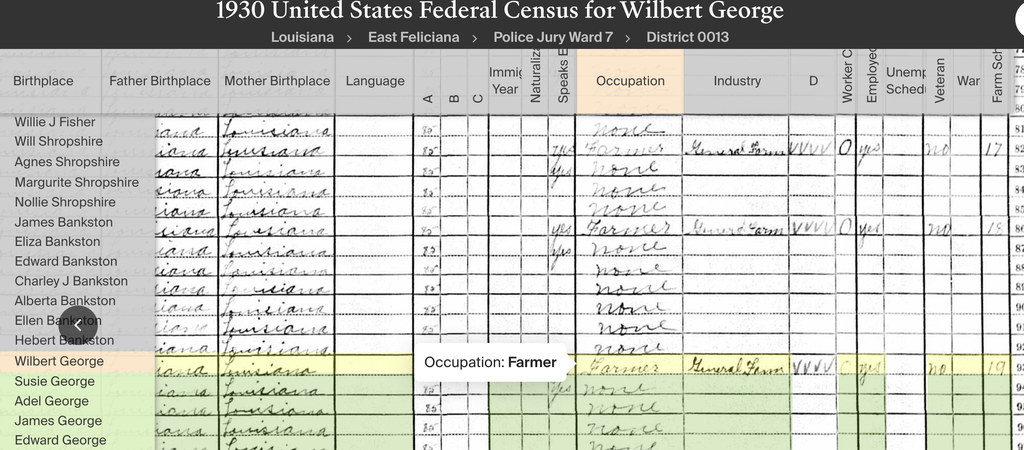

While we aren’t genetically related, we did find out that our ancestry converges in an obscure, teeny-tiny southern town: Washington County, Mississippi. In my family line, Washington County, Mississippi (which would later split and become part of Sharkey County), is a part of my blood by way of birth, since my great-grandmother Eliza Lightfoot was born there in 1911. For Amber, the county is shadowed by her own family tragedy. Her great-grandfather Wilbert George and his son were tragically killed in a car accident in the same county in 1962.

By the time of George’s death, my great-grandma had already left the horrors of Mississippi behind for life up North in Ohio. When my great-grandma was alive (she died at 103 years old), she often talked about picking cotton under the scorching heat for pennies, and she described the horrors of witnessing lynched Black men hanging from trees in her local town of Cary. The harrowing tales my great-grandma told me as a child about her decades of southern living explains why Nina Simone’s 1964 Civil Rights anthem was aptly titled, “Mississippi Goddam.” The lyrics go, “Alabama’s gotten me so upset. Tennessee made me lose my rest. And everybody knows about Mississippi, Goddam.”

While living in Mississippi, Eliza was a sharecropper, a dehumanizing labor system implemented after slavery was abolished in the South. When my grandma, Willa Mae, was born in 1932, my great-grandma said she would pick cotton with her newborn baby on her back. We found out that Eliza labored less than 200 miles north of East Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, where Amber’s great-grandfather Wilbert George was working as a farmhand, too, according to 1930s census data I acquired from Ancestry.com.

So that’s where our stories converge, in the swamplands of the Deep South along the Mississippi river where cotton was king and racial violence was common. Two generations later, our family’s lines would regionally meet again, at a swanky Los Angeles university. Ancestors, alive once again, in great-granddaughters who could become college-educated and never be forced to plow and pick.

I view me and Amber’s shared history with pride, knowing that we both have ancestors who at one point, called the low wetlands of the south, home. And maybe that’s why we can dive deep together as friends. Our ancestral familiarity with what it’s like to wade in swamp water and survive to tell the tale comes with a side of cornbread, red beans, and rice. We share soul food, literally and figuratively.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

My First Time Cooking For Juneteenth

We Need Global Black Liberation Now